Lesson 1.2 - Discharges and Poles

Part 1: What does the word electricity mean?

From the Merriam-Webster dictionary:

“Electricity – a fundamental form of energy observable in positive and negative forms that occurs naturally (as in lighting) or is produced (as in a generator) and that is expressed in terms of the movement and interaction of electrons”

Although this definition uses lots of big words and general phrases it does tell us a lot about the general idea of the purpose and functionality in our world as well as give us some insight into where we see it every day. Electricity is a form of energy, that is the first and most important part of this definition. The part which goes along with this is the last sentence which discusses how this energy is expressed in terms of the movement and interaction of electrons. The movement of electrons is a generated and usable form of energy, much like how a moving roller coaster creates large

amounts of kinetic energy. Electrical energy is generated by the movement of electrons from a more negatively charged source to a more positively

charged recipient. This movement occurs due to Coulomb’s law which was discussed more in depth in Lesson 1.1 but essentially explains why and how negatively and positively charged particles attract each other and repel similarly charged ions. This movement generates energy which can be harnessed and used, and the Merriam-Webster definition gives us a few examples of this. One is naturally occurring electrical sources like the given example of lighting, or manually produced sources of electricity as in human-produced generators. Although these are two types of ways electricity can be found in the lesson below we will discuss the two distinct types of electron flow.

Part 2: Where does electric movement actually start?

The term electricity is more broad than how we think of it in our day to day lives. It does not just exist in the form of charging our phones or supporting our household appliances. Lightning is an example of electricity. The same is true for when you sub your feet on a carpet floor and shock someone. Although these are all examples of electricity, they are each an example of a category of electricity. These two categories are static electricity and electrical current. Below we will discuss static electricity, and next lesson we will apply this learning to understand electrical current.

Static Electricity... what is it really?:

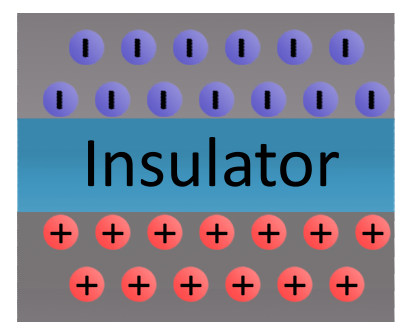

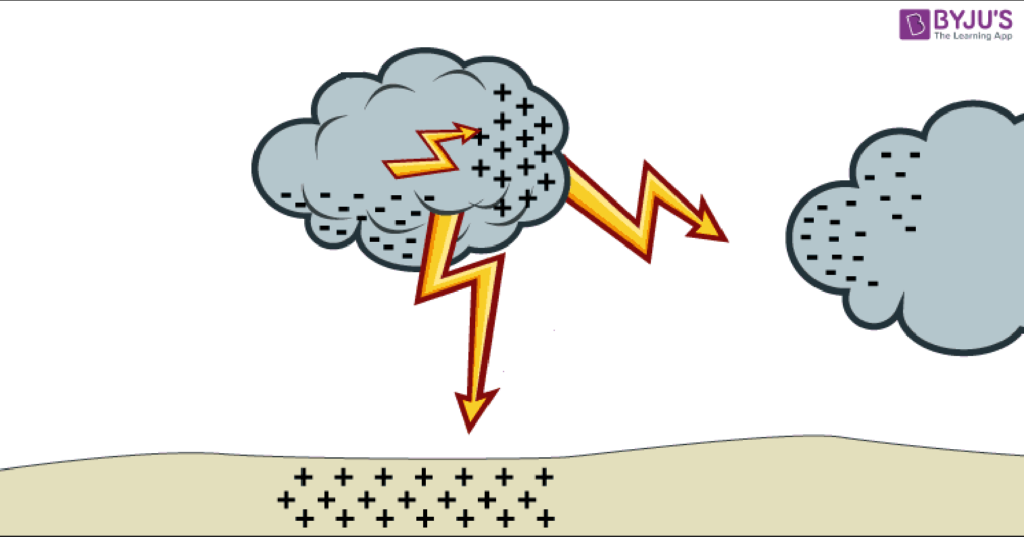

Static electricity might not be what charges our electrical devices and circuits, but we still see it almost every day. When you see a bolt of lightning, or when your hair stands on end, both are examples of static electricity. But what is it? Static electricity is caused by a buildup of charged particles in two substances. Let’s imagine for the sake of an example that these are two sheets of metal. The only issue is that the two sheets are separated by an insulator. In this case our insulator is the air as it cannot conduct electricity. On each side the oppositely charged particles begin to attract with one sheet having a large collection of positively charged particles and one having a large collection of negatively charged particles. This is depicted in the figure to the right.

As time passes more and more particles build up, until eventually their attraction overcomes the barrier of the insulator and a static discharge occurs. Within this static discharge is a quick, burst, of electrical flow through an insulator between two charged objects. Let’s look at a real example.

Lightning is one of the best examples of static electricity that we see everyday. Lightning is the static discharge between clouds and the ground, between two clouds(inter-cloud), or within a cloud itself(intra-cloud). Charges buildup first within the cloud when very tiny ice and water particles rub against each other. This is why lightning comes from rainclouds because as water descends and collects within a cloud it rubs against all of the surrounding particles on the way down. The more these particles start to rub against each other, the more negative charges begin to build up at the bottom of a cloud. These begin attracting positive charges to the surface of the ground. A strike of lightning occurs when the electrical difference grows so great that a static discharge occurs through the air. Lightning is portrayed as “striking the ground” since the negatively charged particles in the cloud

are where the discharge begins to flow from. Lightning between clouds occurs in much the same way. In this case though as one cloud begins to develop a collection of negatively charged particles near the bottom of the cloud, it also builds up a collection of positively charged particles on the opposite side in reaction. These positively charged areas will then be attracted to the negatively charged particles within another cloud causing an inter-cloud lightning strike. The third form of lightning occurs within a single cloud. It is much like inter-cloud discharges, however this time the positive and negatively charged areas of a cloud are insulated by contained air and water particles. As charged particles collect sometimes a discharge will occur within the cloud before the charges grow great enough to cause a could to ground strike or an inter-cloud strike.

Activity: Static electricity, Balloons, and your ... hair?

Materials needed:

- Balloons (latex or rubber balloons work best, but mylar is a doable alternative if you are allergic it just will not work as well)

- A method to inflate these balloons

- Cotton clothing or a towel

- A piece of string about 4-5 feet long

Procedure:

Part 1: Sticky Balloons

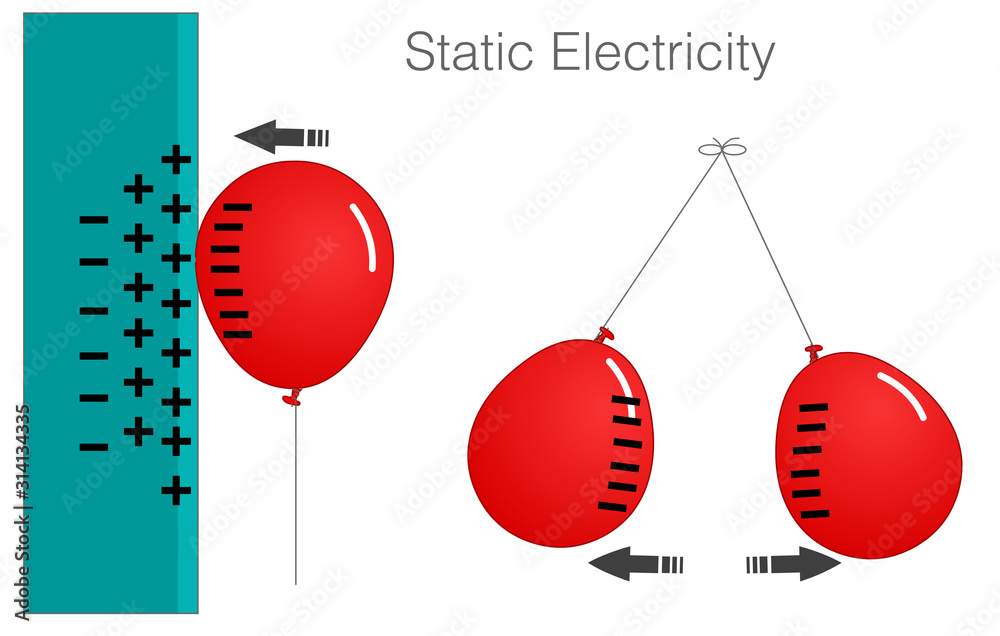

To start our exploration of static electricity we will use balloons to show us how charged particles will react. Balloons are useful here since if they are just rubbed correctly they can quickly become charged. For this first part we will look at static attraction. This occurs when two oppositely charged areas of objects touch and therefore they “stick” together much like magnets. To begin take your balloon and rub it against either your shirt or the towel you are using. Make sure you rub it back and forth quickly to build up charge on the surface of the balloon. Now take the charged area of the balloon and push it on your wall gently. Now let go! If it doesn’t stick try rubbing the balloon again for longer to make sure enough charge has built up. We can see why this works in the diagram below, but it looks like magic. We just stuck a balloon to a wall with nothing but a piece of cloth!

Part 2: The Balloons won’t touch

For this part we will need two balloons as well as the same cloth or piece of clothing. We will also make use of the string. Make sure your balloons are still inflated. Now tie the string to the knot at the end of each balloon. Now either grab a partner or do both balloons yourself, but we need to rub both of the balloons on the cloth on the side where the balloons touch when held by the middle of the string (as shown in the diagram below). When you’re done rubbing the balloons, lift them from the center of the string. The balloons won’t touch! This is an example of a static repel. When two surfaces with the same general charge come into contact they will always repel one another.

Part 3: Crazy Hair

For this part, we will need one inflated balloon, and your hair! Start by taking the balloon and rubbing it against the top of your hair. Make sure you rub it for a little while to build up charge.(keep in mind that if you have curly/frizzy hair your hair already has some static charge and this may not work). Now pull the balloon off and look at your crazy hairdo! This happens because as the balloon rubbed against your hair it caused each hair to gain a slight positive charge. When the balloon is removed each hair repels the other and causes them to stand on end to try and make this distnce as great as possible. This is another example of a static repel.

Make Sure to send photos of you doing the activity, and your crazy hairdos, to lookingbeyond@asteppastobvious.com, to get featured here.

Diagram:

Gallery:

The Step Beyond: How do negative and positive "sides" even form?

We know that static discharges of electricity occur when a negatively charged surface interacts with a positively charged surface, but how does this charge difference even form to begin with. Well this can be found in the atom structure itself.

You might’ve noticed that the material we used in the home experiment was rubber balloons. But wait, rubber doesn’t conduct electricity? Does it? In short no, the materials involved in creating a static discharge are not actually charged or conducting electricity in the same way as metals would. It’s not like the clouds draw power to create a strike of lightning. Instead a process called Polarization occurs.

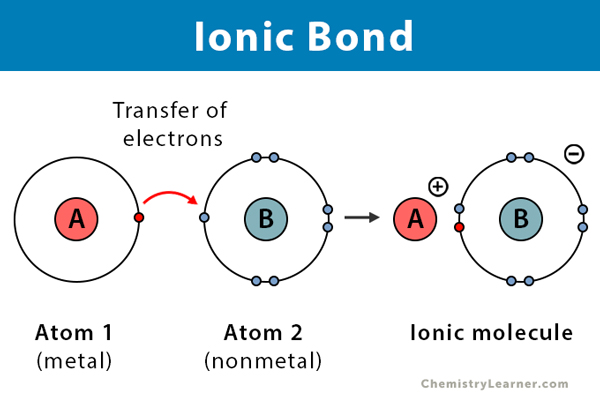

The two types of bonds:

To understand polarization we must first look at the types of bonds which atoms can form. In short there are two main types of atomic bonds that form to create molecules. The first is an ionic bond. This type of bond occurs between a nonmetal and metal. These are split on the periodic table to the right. In short, metals are prone to becoming positive ions and nonmetals are more prone to forming negative ions. All of them do this to fill their orbitals in reference to the noble gasses who compose the furthest right column which have full orbitals. For example, Oxygen is two columns away from the noble gas Neon and since it is a nonmetal, in order to form an ionic bond it would form an

O(-2) ion, while Aluminum which is 3 columns past the noble gas neon(if you go down a row following the increase of atomic numbers)

and is a metal so it would form an Al(+3) ion. In an ionic bond these would then come together to even out the charges forming a molecule. For example 3 O(-2)’s would combine with 2 Al(-3)’s since 3(-2) + 2(-3) = 0. Ionic bonds always have a net charge of zero. So this molecule would be Al2O3 or Aluminum Oxide. In this situation the electrons that the aluminum gives up are received by the oxygen. In an ionic bond this is always true as the charge can’t come from nowhere. The metal always gives up ions and the nonmetal always receives them and then their respective charge differences create a bond between them.

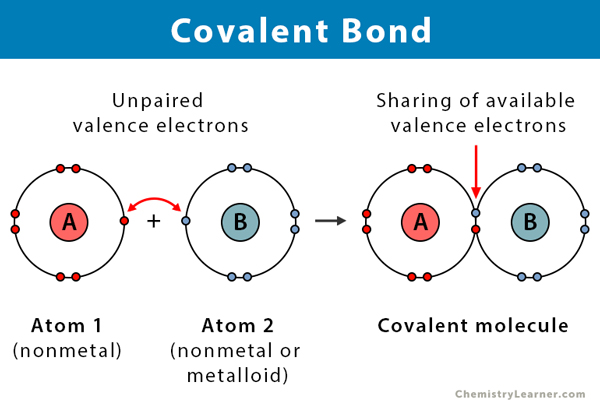

The second type of bond is a covalent bond. This type of bond occurs between two nonmetals. Since nonmetals all need to receive electrons to fill their orbitals and bond in a covalent bond the nonmetals share electrons. They do this in pairs. Let’s take for an example the molecule of water: H2O. One rule with covalent molecule forming is that a hydrogen only needs one extra electron to fill its orbital so it only ever has one shared pair. This means it shares both its original electron with the other atom but also shares one of the other atom’s electrons as a part of the shared pair. Oxygen needs 2 outside electrons so it needs to form two pairs to gain these two. Since a Hydrogen can only form one pair this means for Oxygen and Hydrogen to combine there needs to be 2 hydrogens with each oxygen so that the pairs can form and the molecule is stable.

What is Electronegativity?

Polarization occurs due to a unique trait of a certain type of covalent molecule: polar covalent molecules. Makes sense, right? But to understand polar covalent molecules we must talk about another property off all elements, electronegativity.

Electronegativity is an atomic property very closely related to ionization energy(discussed in lesson 1.1). Electronegativity is a measure of how strongly an atom attracts its surrounding electrons and how this relates to bonds. If the correlation was not already apparent, the higher the ionization energy, the higher the electronegativity. To the right is a periodic table with all of the measured electronegativities of each element. What does this property mean though? Well in a covalent bond electrons are shared. If both atoms have the same electronegativity then they will have the same pull on the shared electrons and they will be spread evenly. However if there is a difference in the two or more electronegativities in a molecule then one atom will have a greater pull on the shared electrons than the other. This leads to one side with a concentrated number of electrons and one with less. We call these molecules polar as they have a more positively charged side and a more negatively charged side. The greater the difference the greater the polarity is, however in the case that the two electronegativities are the same those atoms are called nonpolar

Interactive: "Molecule Polarity"

For this interactive we will be using the PHET "Molecule Polarity" interactive. This interactive is part of the PHET interactive simulations developed by Colorado University at Boulder and can be found here: https://phet.colorado.edu/sims/cheerpj/molecule-polarity/latest/molecule-polarity.html?simulation=molecule-polarity

To understand this interactive we must first learn what a few words mean in relation to polarity. The first of these is the name for the symbol we use to show the direction of polarity. This is called the dipole and is depicted as an arrow with a plus at the backend representing that the arrow points in the negative direction and away from the positive side. Since polarity is a vector this arrow represents direction and its length represents how strong the polarity is. A dipole can either be a bond dipole, meaning it is the dipole of a singular bond, or a molecular dipole meaning it is the average of the overall bond dipoles.

Now we can open the simulation. Let’s explore molecular polarity with just two atoms. Make sure you are on the two atoms tab, with bond dipole and partial charges turned on. Now let’s see what happens if we change an atom’s electronegativity. Make sure you turn that of atom A all the way down so we can easily view this. Now start with atom B’s all the way down as well. Here we don’t see anything! This is because this is now a nonpolar atom as the electronegativities are equal. Now begin to increase the electronegativity of atom B. The dipole increases in this direction and so do the partial charge. Now try reversing it. The same thing happens in the opposite direction. This is an example of how electronegativity can polarize a single bond.

It’s important to realize though what this dipole points to and away from. The dipole always points toward the more negative side as it points to the side holding the most electrons or most electronegative. This is why we mark the opposite side with a plus as well as to symbolize the origin of the arrow. Now try one of the other features to look more into what this all really means. Click on the box next to bond character. Realize that when you set the electronegativities of each atom to the same level the bond character slider shifts to more covalent. This is because electrons are being shared more evenly. Now set the electronegativities to a respective gap. Notice how now the bond appears more ionic as electrons shift more toward one side of the molecule. This is a good demonstrative for how a polarized atom leads to a charged state.

Click to the three atoms tab and play around with the electronegativities and watch how the dipole reacts. This is a more realistic perception of dipoles. They are not always cut and dry, but they are always calculable. And yet if you click over one more time to the real atoms tab you can look into the dipoles of real atoms all around us. There is one more thing to realize. Set the atom type to water first. Now turn on both partial charges, bond dipoles and the molecular dipole. Notice how if you were to add the partial charges of the hydrogen they add up to 0.76, greater than the 0.75 magnitude of the oxygen. And yet the dipole points away. This is because charges only matter within bonds because electronegativity rules only act within singular bonds. So to calculate a molecule dipole you have to first calculate the bond dipoles and then find the vector resultant of the two. You can play around with other molecules but this is the basis for how covalent molecules become charged to allow for static discharge

The Last Step: How do the sides really form?

Above we discuss electronegativity and how it can create polar molecules but how does this actually lead to static discharge if molecules are all over the place and dipoles aren’t aligned. Well one way is to align them through friction. When two objects rub together a process known as triboelectic charging occurs. The more electron affinitive polar atoms are drawn to the electron clouds of the other object they are in contact with and rubbing against. As they are drawn toward these electrons the dipoles of the molecules begin to align with each other and hold onto more electrons from the opposing side charging their surface. As this process continues one side becomes strongly charged. It will then attract those molecules it was rubbing against which are now charged more positively on the exterior. Other versions of triboelectric charging however can be internal like within clouds. As molecules rub against each other some molecules pick up more electrons and shift down in the cloud. As this process continues a negative region collects at the bottom of the cloud and as discussed above this reacts with the positively charged ground to create a discharge. Another way to charge the sides to create a discharge is to use a process known as induction. In this you make use of a previously charged object to charge another. If you know one side of an object is negatively charged you can use that side near another object to draw a positive pole near the contact within the other object. Although there are a few other methods the ones discussed above are the basics for how static discharges develop and react around us.

An Intro Into What all of This Means Beyond the Discharge

Understanding Conduction and Grounds

So far we talked about what happens when we put a charged object near one that isn’t charged, however we haven’t discussed the question of contact. When a charged object or surface makes contact with another things become interesting. The best way to tackle this is to look at an example. Let’s say the surface of a balloon holds an excess of electrons, also known as a negative charge. Now let’s say we bring that balloon to touch a neutral metal sphere. Since metal can conduct, as it is called, a charge, it will receive the charged ions from the balloon(in this case electrons) until an even charge is reached. This is what the process known as conduction is. If the object were positively charged electrons would jump the opposite direction to create an equal positive charge across objects.

One thing constant in all of this is the total charge of the system. In physics the term system is used to refer to the objects being discussed, while the environment describes everything that is not the system. In the discussion above the balloon and metal object would make up the system. One interesting feature of charge though is that, in what is known as an isolated system where no energy or mass enters or leaves the system from the environment, it does not change. If the total charge of a system starts out as +3, that charge can be spread all kinds of ways but the total will always be +3. This law is known as the Law of Conservation of charge. We can see this clearly with a set of two color marbles or any objects. Choose one color to be positive and one to be negative. Now count what the total charge of your system is(how many more of whichever type you have more of). Although you can group these to make groups with vastly different charges the total charge is always the same.

Now while it may seem like charge will always be shared evenly between two objects, this is not the case. Charges are shared more often based on the size, or mass, of the objects being discussed. If you have a small charged object and a large neutral one that touch the large one will assume almost all of the charge. However the Law of Conservation of Charge is maintained. However this concept is important for one action – grounding a charge. Let’s say we have a system where we want to remove a charge. Due to this idea one could simply find a large enough object to take on the majority of the charge. Let’s look at an example.

When kids go down a slide their clothes rub against the metal rivets and charge them triboelectricly. As the charge becomes greater a kid touches one with their skin and feels a shock. What happened? That kid conducted the charge from the rivet into their finger, and because their mass is effectively so much greater they grounded that charge leaving only a remnant in the rivet. But why doesn’t this hurt the kid. Obviously the human body isn’t meant to hold a charge. That is why we get electrocuted by high voltages. However again since the mass of the child is so much more than that of the rivet what may have been a significant charge on the rivet is lessened by the size of the child. Also through interactions with the environment the child gives off the charge and retains neutrality.

Grounding is still a form of conduction, but rather than being conduction within a system it is the conduction of charge out of the system or into a larger one. One crucial thing to realize with all forms of conduction though is that not all materials can conduct electricity. Conductivity is something that we will discuss more in the next lesson. Right now it is important to grasp the concept of conduction, however many objects and materials around us do not have this property.

Interactive: "Charging" - Keeping the Balance

For this interactive we will be using "the Physics Classroom"'s "Charging" interactive. This interactive is part of the "The Physics Classroom"'s interactive simulations developed online and can be found here: https://www.physicsclassroom.com/Physics-Interactives/Static-Electricity/Charging/Charging-Interactive

This interactive will force you to apply your knowledge of attractive and repulsive coulombic forces and use induction and conduction to charge objects to specific levels. In this interactive you are given two bars, which you can move around, a balloon with a negative charge, and a ground source. In the practice tab play with these items by moving them around the screen. Try connecting the two blocks to see the electrons move around. Try moving the balloon near this grouping to see the charges shift. Now watch what happens when you connect the grounding source. Try picking two charges and trying to make them with the two. Once you feel comfortable you can move on.

Once you get a feel for how these tools work move on to the play tab. Now comes the fun part. Under a timer race to set the blocks to the charges listed below. Try and come up with strategies to move the charges how you need. See if you can figure out the puzzle fast enough. Keep playing with this interactive to better your understanding of how the movement of charges and polarization of objects works. See if you can get all three stars in as close to thirty seconds as possible.

Another Step Beyond: How do we measure all of this?

For centuries the instruments humans have used to measure electricity have evolved immensely. Beginning all the way back in the 17th century, the versorium was the first tool of this kind with true capability. It acted much like a magnetic compass would, using a needle and base, and turning away from any distinguishable charge. While this allowed scientists to see charges existed and view subtle differences in charge magnitudes, it could not tell them the true size of the charge nor could it distinguish anything about polarity.

Next would be the Pith Ball electroscope. Electroscope is the term scientists use to refer to these types of measuring devices. This electroscope was composed of a base for support and then silk or silver wire reaching out to a ball made of pith, a plan material which as a nonconductor would polarize in the presence of a charge. Because of this polarization one could tell if an object was charged based on whether the pith ball was drawn toward the object or not. If there was attraction then there was a charge, but if not there was none. However this still possessed the issue of a weak ability to distinguish type of charge and magnitude.

Then would come the innovation of the gold leaf electroscope. Two sheets of conductive gold leaf were first connected to a brass rod. That rod would be situated into a sealed glass container so that the pieces of gold leaf hung in the middle. above all of this the brass rod would be connected to another conductive metal disk. As a charged object touched the disk the charge would flow throughout and be reflected in the gold leaf sheets. A higher charge, the farther spread apart the two sheets would be. On the side walls were grounding strips to take charge out of the system if the gold leaf sheets spread so far apart to reach the sides of the container so that the sheets would not tear. Also the sealed glass would later become a vacuum chamber in more precise designs. Although still not capable of displaying charge type, the gold leaf electroscope

As time has progressed, we now are able to use electronic voltmeters to test for electrostatic charges and all of their qualities. But how do we measure beyond this? Well with the same ideas brough up in the lass lesson. Using coulomb’s law we can test for the strength of a charge and the force it gives off. But what is crucial to measuring static electricity is something to be brought up very soon in lesson three: electric fields…

References

Beaty, W. J. (2005). Determining electrostatic charge polarity2005 W. Beaty. Finding polarity of Static Electricity. http://amasci.com/emotor/polarity.html#:~:text=To%20determine%20polarity%2C%20turn%20on,will%20indicate%20the%20object’s%20polarity

Let’s Talk Science. (2020, November 19). Introduction to static electricity. https://letstalkscience.ca/educational-resources/backgrounders/introduction-static-electricity

The Physics Classroom. (2016). Physics tutorial: Static electricity. https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/estatics

Science Reference Section, Library of Congress. (2019a, November 19). How does static electricity work?. The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/everyday-mysteries/physics/item/how-does-static-electricity-work/#:~:text=Static%20electricity%20is%20the%20result,them%20is%20through%20a%20circuit.

Science Reference Section, Library of Congress. (2019b, November 19). How does static electricity work?. The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/everyday-mysteries/physics/item/how-does-static-electricity-work/#:~:text=Static%20electricity%20is%20the%20result,them%20is%20through%20a%20circuit.