Lesson 1.1 - Looking at the atom

Part 1: The atom and subatomic particles

Atoms as defined by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary are “the basic unit of a chemical element.” Atoms are all around and in us. Atoms are, well really everything. “The Atom” is the name which scientists use to refer to the basic unit that makes up all things around us and yet within an atom there are still more parts. For reference, let’s imagine that you want to drive on the interstate. Well everything that drives on the interstate is a motor vehicle, and yet even though these vehicles all share this similarity each has its own unique parts and model that make it up. Within an atom there are three particles: protons, neutrons, and electrons.

The Proton:

The proton is the first of the subatomic particles. Atoms consist of two parts altogether: the nucleus and the surrounding orbitals. Protons are located in the nucleus. Protons are particles with what is called a positive charge. This means that they will draw negatively charged particles towards them. The number of protons an atom has determines what element it is. Each element has unique properties which are caused by these differing number of protons

The Electron:

The electron is the smallest of the three subatomic particles, and is located in the orbitals surrounding the nucleus. In the same way our Earth revolves around the Sun, electrons revolve around the nucleus. Electrons are negatively charged particles, which means they are held in orbit by the difference in charges between them and the positively charged protons in the nucleus. For an atom to be stable it must have an equal number of electrons and protons. If an atom loses or gains electrons, instead of changing what element it is like with protons, it becomes what’s called an ion. This means that the atom is still the same element but it now has a charge. If an atom loses one electron for example it would have a charge of +1 since it now has 1 less negatively charged particle. On the other hand if it were to gain two electrons it would have a charge of -2 as it gained two extra negatively charged particles

The Neutron:

The neutron is the third and heaviest of the three subatomic particles. Unlike the other two neutrons have no atomic charge and therefore have little effect on the type or ionic state of the atom. Neutrons do play a part though in atomic weight. Neutrons are located in the nucleus along with the protons and weigh almost the same amount as a proton. In a regular atom the number of neutrons can vary. Each element has a unique number of neutrons in its nucleus in its most common form. However there are also often atoms that don’t fit this regular number. These atoms with extra, or less neutrons, then their elements most common form are called isotopes. For example the most common form of the natural element Carbon is Carbon-12, named this because it has 6 protons and 6 neutrons so its atomic weight is approximately 12 atomic measurement units. Although Carbon-12 is the most common when scientists do certain procedures such as Carbon dating they actually look for an isotope called Carbon-14, which has two more neutrons, as the amount can indicate the age of an organic object, More neutrons also means a heavier atom. For another example a common home issue in plumbing and showers is called “heavy water”. Regular water is composed of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. When water becomes “heavy” it means that the hydrogen atoms, which regularly contain just a proton and an electron, now contain a neutron as well, making the atoms weigh twice as much. This isotope of hydrogen is called Deuterium and this new Deuterium-oxide or heavy water can create issues when ingested. In small amounts it is fine but when taken in in large amounts that extra weight can cause a slow in bodily reactions which can cause issues. So altogether while neutrons might not have an effect on an atoms identity or charge they can certainly affect it’s weight and reactability.

The Periodic Table:

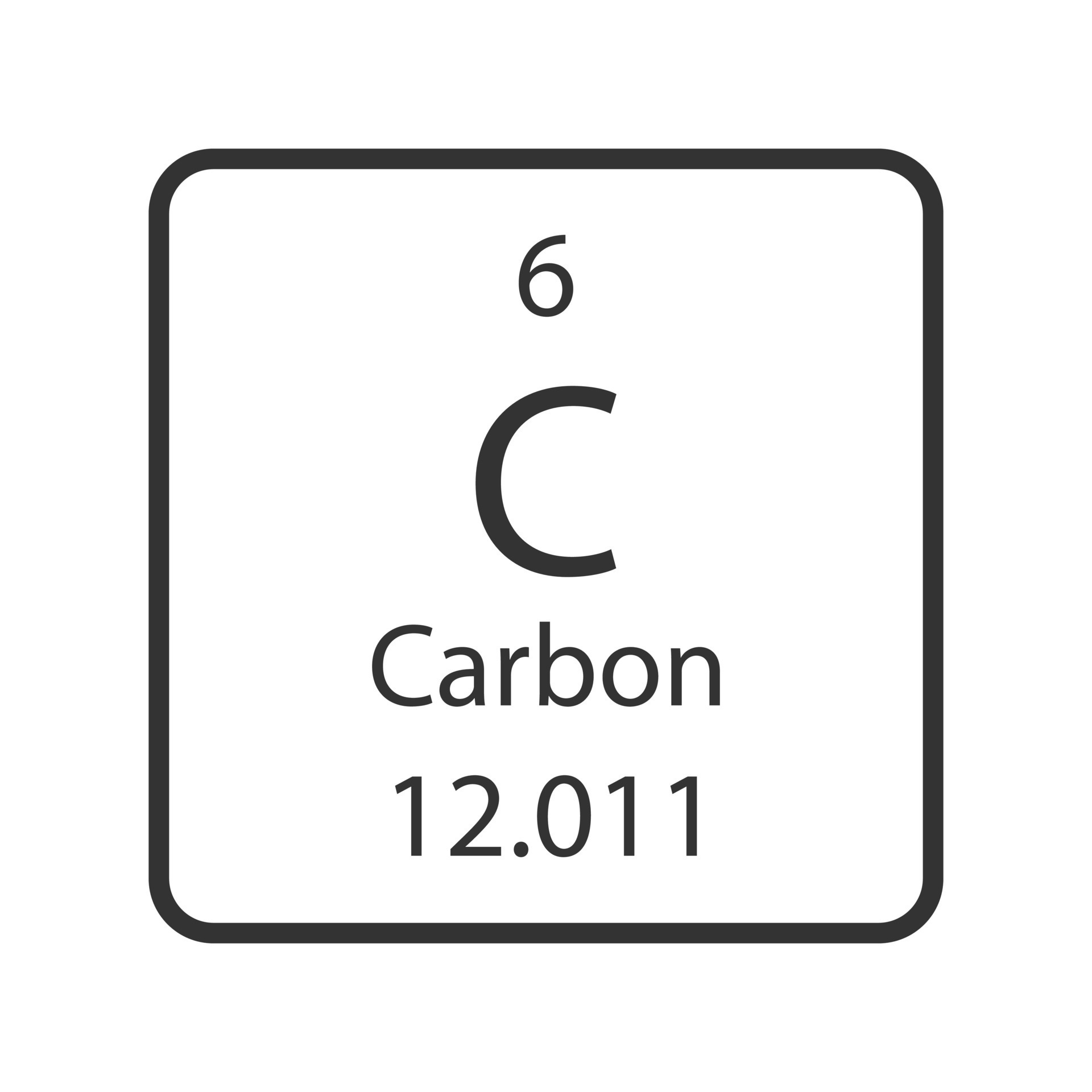

Many of us have seen this table before, and if not you will almost certainly see it in high school chemistry and onward. The periodic table is a visual organization of every natural element we have discovered, which is currently a total of 118 elements. Each element is separated by its number of protons. This number is called the atoms “atomic number”. For example Hydrogen has only one proton so it is the first element with an atomic number of 1, while an atom of Krypton has 36 protons and therefore is the 36th element on the table with an atomic number of 36. Because of this if an atom changes how many protons it has then it also changes what element it is. An atom’s protons determine its identity. This atomic number, since it is the number of protons, is also the number of electrons in a stable atom of the

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/PeriodicTableoftheElements-5c3648e546e0fb0001ba3a0a.jpg)

element. The periodic table also gives each element its own alphabetical symbol. These symbols can be comprised of either one or two letters. Also, some of the symbols make sense with the element name and some don’t. For example, the symbol for Carbon is “C”, while the symbol for Tungsten is “W” and the symbol for lead is “Pb”. Regardless, in these symbols the first letter is always capitalized and any following letters are lowercase.

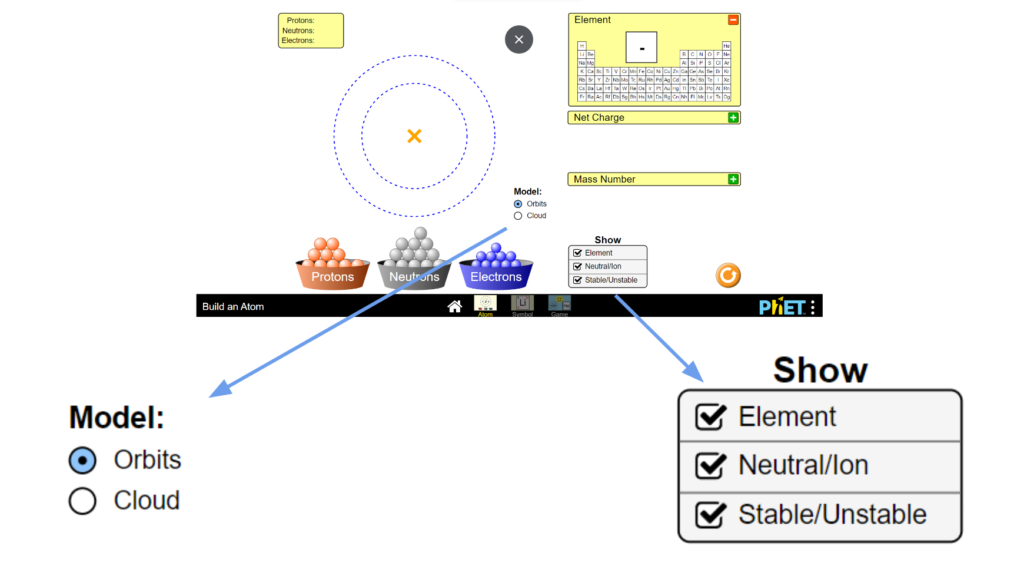

Interactive: Lets Make an Atom!

For this interactive we will be using the PHET "Build an Atom" interactive. This interactive is part of the PHET interactive simulations developed by Colorado University at Boulder and can be found here: https://phet.colorado.edu/sims/html/build-an-atom/latest/build-an-atom_all.html

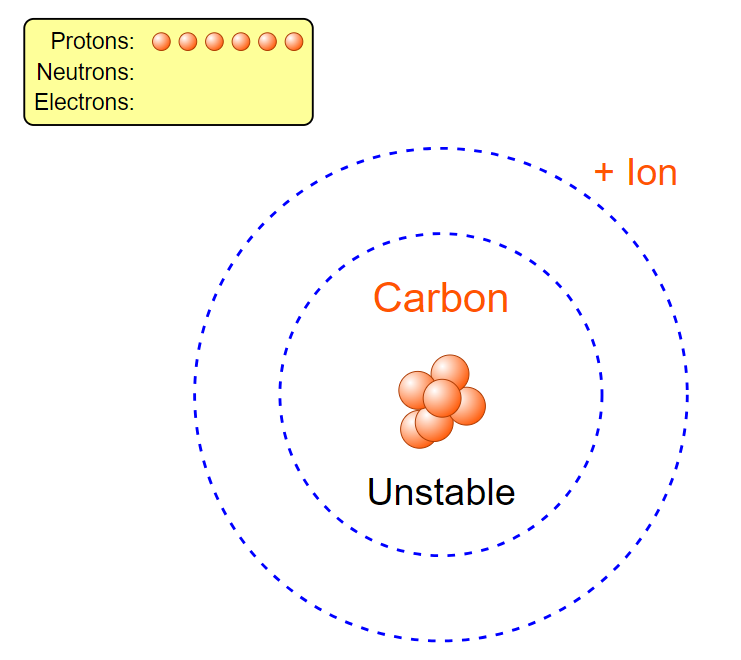

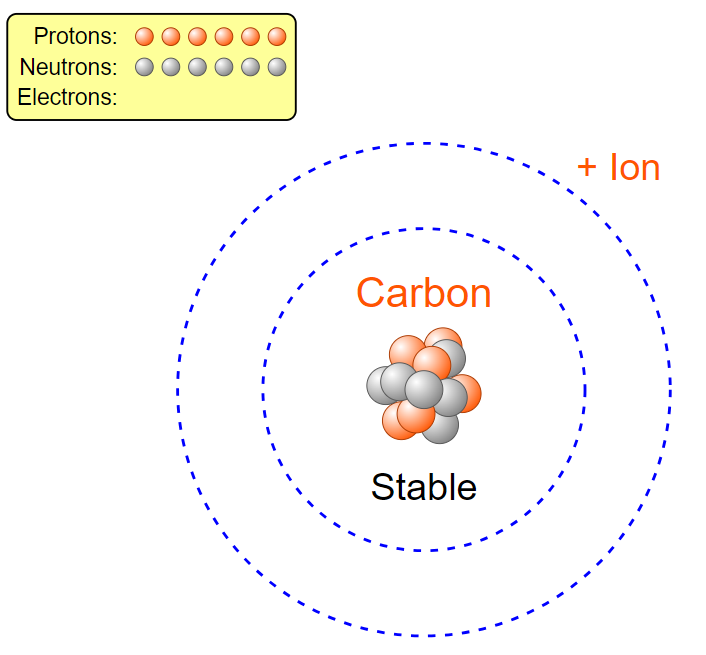

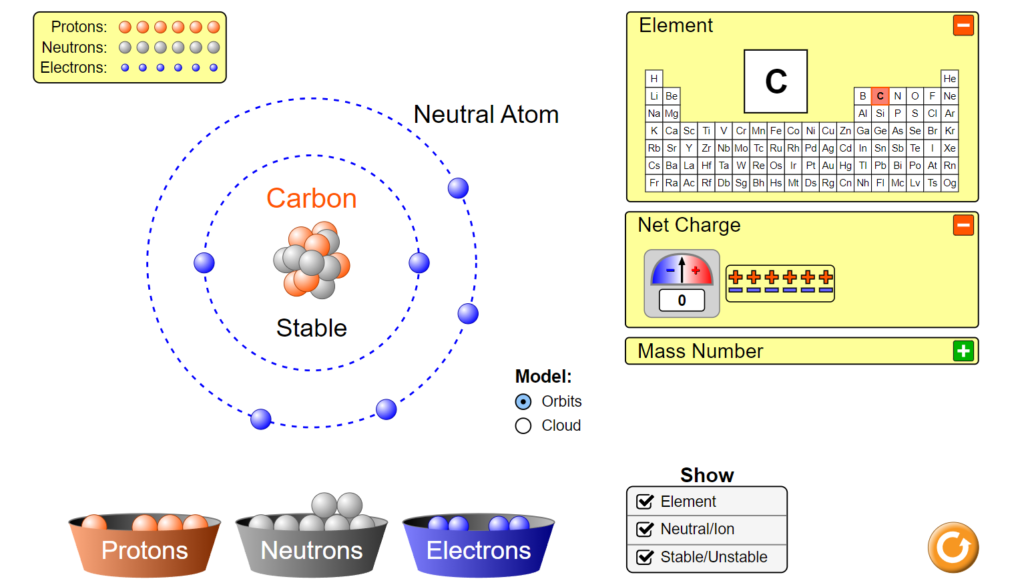

To start, first pull up the interactive and select the first, “atom” tab to begin. You should then see this atom builder dashboard. In this part of the interactive you are able to drag protons, electrons, and neutrons into the field to create atoms. The interactive will then display the element, charge, its stability, and its mass. in order to begin make sure that you have checked the boxes shown in the picture. This means to make sure that you have selected “orbits” for the Model option and have turned on all three checkboxes under the “Show tab”. Let’s start by looking at the field where we can place different particles. When looking at this we

can see both a center yellow cross and two gray rings surrounding it. This yellow cross is for our nucleus, so that is where we can drag our protons and neutrons! The rings on the other hand are meant to represent electron orbitals and so they are where we will drag electrons. Let’s start by making

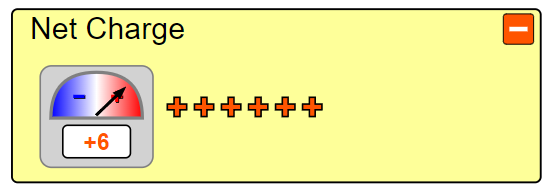

a carbon atom. In order to do this we must first look at how many of each particle a Carbon atom even has. Well according to Carbon’s periodic table entry we can see it has an atomic number of six, from which we can determine it has six protons. Let’s go ahead and drag these 6 protons from the proton bin onto the center “x”. Hey! Now it says we have Carbon, but wait, its unstable. To solve that we can look at the neutrons. When atoms don’t have a viable number of neutrons they can become unstable and break apart, and we don’t want that here. Let’s again look at the periodic table entry. Carbon has a mass of about 12 amu. Since electrons have a nearly negligible weight and protons and neutrons each have a weight of approximately 1 amu we can find the number of neutrons we need. Since total we have 12 amu we can subtract off the 6amu from our 6 protons which leaves us with 6 amu of neutrons or six neutrons. Let’s go ahead and add those now. Now it’s stable! But wait, let’s click the plus by the net charge tab. Our atom isn’t neutral and has a charge of +6. Normal atoms in an ionic state will search for electrons so that they can become stable as quickly as possible. Let’s make our atom stable. If we currently have a +6 charge we need a -6 to balance it out. Since each electron has a -1 charge we would need 6 electrons to balance that out. Let’s go ahead and add those now. Now we have a stable, neutral Carbon atom.

Challenge: In the symbol tab you can see that instead of physically displaying the numbers of each particle the numbers appear as they would in a periodic table entry. Try and see if you can figure out which number is affected by which changes. For more information check here:

https://letstalkscience.ca/educational-resources/backgrounders/introduction-periodic-table-elements

Extra Practice: For an extra challenge try the game section. Here you can test your knowledge of how to classify atoms based on their subatomic particle counts!

Part 2: Atomic Forces

One of the largest components of electricity actually stems from the forces within the atom between electrons, and the protons and neutrons in the nucleus. These forces are called electrostatic forces. These forces occur due to the difference in charge between the negative electrons and the positive protons in the nucleus. The overarching law of this is called Coulomb’s Law. It states in general that particles of opposite charges are attracted to each other by certain rules. We will explore this more in the interactive below.

Interactive: Coulomb's Law

For this interactive we will be using the PHET "Coulomb's Law" interactive. This interactive is part of the PHET interactive simulations developed by Colorado University at Boulder and can be found here: https://phet.colorado.edu/sims/html/coulombs-law/latest/coulombs-law_all.html

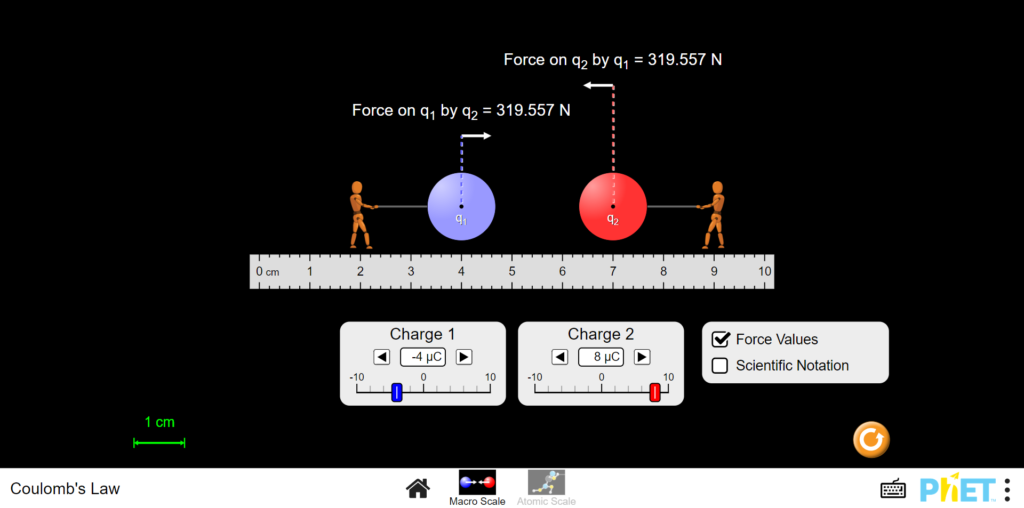

In this interactive we are going to explore in detail, the interactions between charged particles within the atom. To begin we will start by opening the macro scale tab to get a general sense of the rule. On this screen we see all sorts of numbers in symbols. To explain the numbers at the bottom are symbols for charge. The symbol µC is just a symbol for the unit nano-Coulombs which is how scientists measure the charge of an electron. The numbers at the top are the forces on the particles in newtons. On the ruler we can also see measurements of distance. Here we see the distance is in centimeters which can tell us that the whole model is scaled up for our ease of understanding.

Now that we understand the workspace we can start using the interactive. Let’s first view the force that happens when you set one proton and one electron against each other. To view this we can set charge 1 to -1µC and the other to 1µC as if they hold the charge of each particle. Now let’s drag particles over to the right as far as they will go. Here is our maximum force at these charges and it is 45.855 N. Now let’s see what happens when we start moving the negative particle to the left. The force decreases! This is the first rule with coulomb’s law. As distance increases the force increases if charges are constant.

Now let’s test what happens when we change the number of protons in the nucleus. This would be like raising the element. Lets set them to a fixed distance. From here let’s look at their force measurement to remember. Now change the positively charged particle to 4 instead of 1. The force increases! This is due to the greater charge difference between the electron, and in this case, the four protons in the nucleus. In cases like this even if we had four separate electrons each one would experience this same force. This is another rule of Coulomb’s law. As the charge difference increases, so too does the force between particles.

Challenge: look at the atomic tab and pay attention to the difference in the size of the units. These are the units for a real atom!

Why do these rules matter?

One of, if not the most important thing in electricity is the ability for an electron to break off of an atom and move to another one. This occurs most easily when we minimalize the forces between the outermost electron and the protons in the nucleus which contain it.

Orbitals:

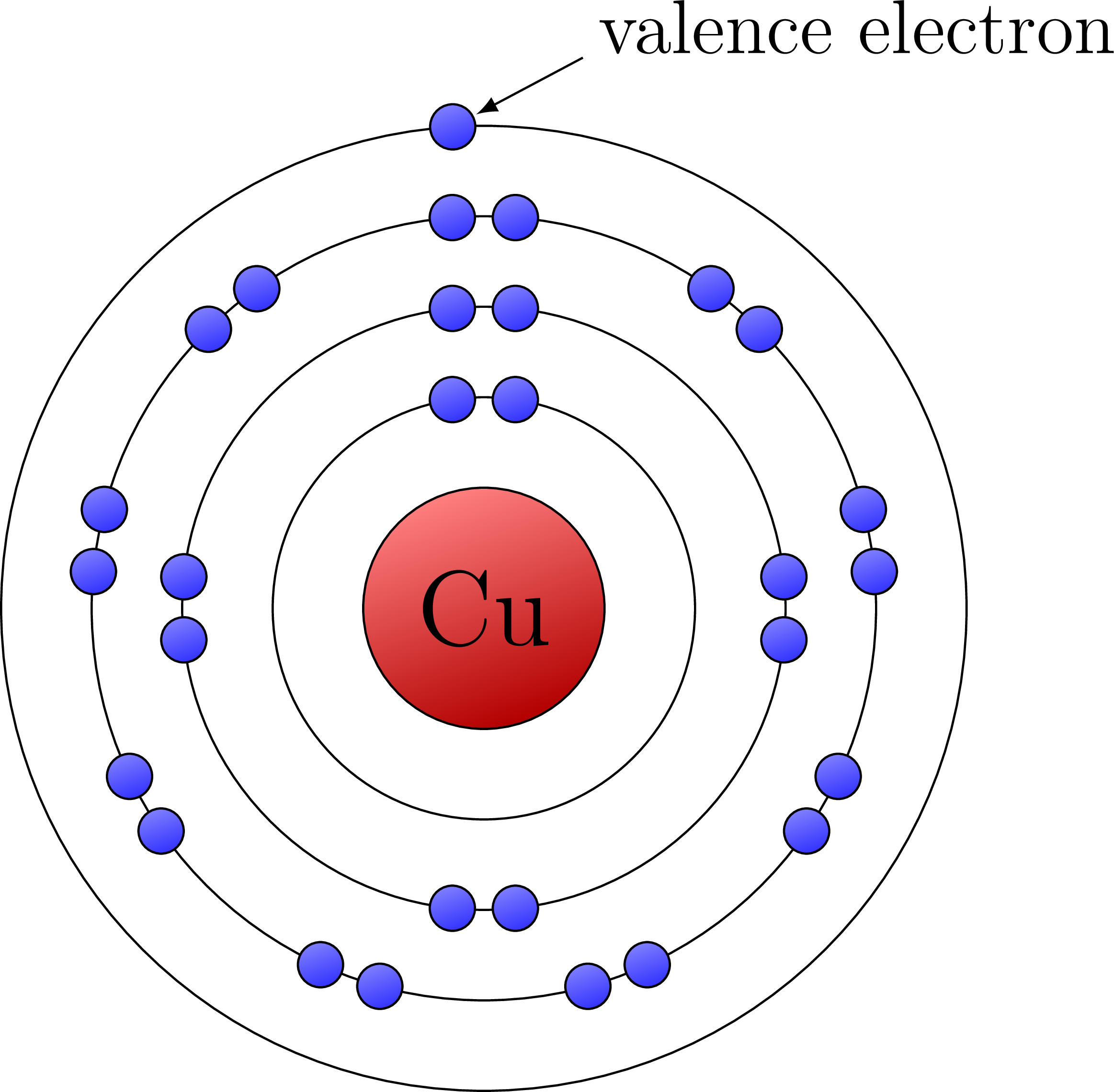

Electrons fill in around the nucleus in a certain order. They fill shells around the nucleus called orbitals. The first orbital can only hold two electrons. The next two orbitals can hold 8 electrons. The next two orbitals hold 18 electrons. These last two orbitals though fill in an irregular patternAll orbitals after this do not follow such a simple pattern, however we will only need as far as the fifth orbital for this unit. These orbitals though, are another way to show the change in distance between electrons and the nucleus. Distance increases as orbitals increases. Also the electrons in the outermost orbital for an atom are called valence electrons. Valence electrons usually have the least force of attraction on them as they are furthest from the protons in the nucleus.

One trend on the periodic table as well follows the orbitals. The first row has two elements. The next two have 8. The next two have 18. Is this pure coincidence? No, as with most scientific coincidences this has meaning. The periodic table is designed this way so that the entire column on the left, known as the noble gasses, have completely full orbitals. This means that with each row the distance between electrons and the nucleus increases. This also means that the size of atoms increases. One thing to keep in mind is that as you move down the periodic table though, the distance increases meaning that valence electrons become more susceptible to becoming free. The other name for this removing force is called ionization energy as it refers to the force it would require to remove an electron and thus make the atom an ion.

A Proton Pattern:

While distance was one factor in making electrons easy to remove, so two was the number of protons pulling on the electron. The more protons the harder it is to separate the electron. This also means the higher the ionization energy. Because of this another pattern appears. As you move left across a row on the periodic table, the proton number increases without an increase in the distance between charged particles. This is just like the second part of the interactive and so as predicted the force increases. From this we can see that as you move across rows on the periodic table the ionization energy rises.

A way scientists view how susceptible atoms are to losing electrons, especially in those elements whose orbitals do not fill in a regular order, is by looking at how many valence electrons the atom has. If it has just one then that means that one electron has a great distance with as few protons in the nucleus as it could have at that distance from the nucleus. If there were two we now could predict that the force has increased because another electron means another proton. This continues as more valence electrons appear. Because of this when scientists look for elements to carry electricity with low ionization energies they usually look to those with only one valence electron.

Copper: A Real World Example:

At this point you may be wondering, what elements actually have just one valence electron. Well let’s look at the most commonly used metal to transfer electronic charges, copper. Copper is special because although it falls in the middle of the periodic table, its orbitals fill in an irregular pattern meaning we end up with just 1 electron in its 4th orbital. Because of this special case(which is due to the way electrons fill shells around the nucleus) copper has a uniquely low ionization energy. Along with that copper is also an abundant metal which is also malleable and can easily be manufactured in the real world. Let’s now see what these electrons look like in a Bohr diagram.

When we talk about what materials are most often used in electrical wiring, the first and greatest answer is copper. This is due to the marked single valence electron which copper has while still not even having a full 3rd orbital. This copper a significantly low Ionization energy making it usable in our real world applications.

At Home Project 1: Element Cube!

Although in this unit we have discussed the element copper and its use, many elements have their own unique uses. Here you can make your very own element cube and get to know another element a little bit better.

Materials:

- Cardboard or Cardstock

- Tape or glue

- Colored paper

- Sharpies or Markers

- Any extra decorative materials ( i.e. tissue paper, pom-poms, glitter, etc.)

- Internet access

Directions:

Step 1: Make your cube! Using either your carboard or cardstock cut 6, 4 inch squares out. Now align these as the 6 faces of your cube and either tape or glue them together to form the cube

Step 2: Research. Using the internet research an element other than copper that interests you. The some time researching this element. This will help for later when you decorate each side

Step 3: Top Face: Now we will start marking up the cube. The first, and most important diagram to display an atom’s structure is a Bohr diagram, named after the scientist who developed the model, Niels Bohr. A Bohr diagram looks much like the one of copper shown above, showing the nucleus, and electrons around it, as well as often the number of protons and neutrons written on the nucleus and the atomic symbol. For this cube you can either print a Bohr diagram or print one out and place or draw it on the top face of your cube.

Step 4: Side 1: For the first of the four sides touching the top of your cube we will put some of the most important information about your element. This should include the number of each subatomic particle, the number of valence electrons, the symbol, the full name, and the atomic mass along with any other valuable numbers or information

Step 5: Sides 2 and 3: for the two sides bordering your first side and the top face, find a practical use of your element for each one. Write about how your element is used and include [pictures or drawings to add to your description.

Step 6: Side 4: For the fourth side bordering the top we will have some more fun! In fact this side is just for fun facts. Find some facts about your element that you haven’t already placed on one of the other sides and write about them here. This could include a severe reactivity with water, or even a bright red color.

Step 7: Bottom face: Although it might seem boring, the bottom face is the most important. This face is here for you to site any sources you might have used to gain information. Remember the internet may be our most useful tool but it doesn’t mean we get to abuse it. Make sure to give any source you used credit.

Step 8: Decorations: Add some finishing touches! Maybe add some tissue paper around the corners or some glitter to the edges. Spice up your cube and make it unique. Try to avoid having too much blank space so that your cube is visually appealing. If you complete your cube and you are proud of it, send a picture to lookingbeyond@asteppastobvious.com and maybe it will get featured on this page!

Gallery

The Step Beyond: How we calculate forces - Coulomb's Law Formula

As you progress through scientific studies, calculating exact values for the electrostatic forces between particles becomes ever more important. Even in the PHET simulation, the Coulomb’s law formula is running behind the scenes calculating all of the displayed forces. Let’s look at the formula for Coulomb’s law, it might seem complicated at first, but we will do our best to work through it. The Coulomb’s law formula is used to measure a force between two particles from Coulombs to Newtons.

Coulomb’s Law Formula:

What does each variable mean:

|F| – This absolute value of the variable F is representing the overall force between the two particles. This force is in Newtons. This can also be written as F with a subscript “elect”. It is in absolute value bars because the value will always be positive and it is up to the calculator to determine whether the two particle should repel or attract based on their starting charges.

q1 – This variable represents the starting charge on particle one in Coulombs. Remember the Phet, the charges on the activity were all in Coulombs. A Coulomb is just a measure or how positive or negative, in this case the first object, is.

q2 – This variable represents the charge of the second object in Coulombs. Both of these are within absolute value bars as the overall charge must be measured as positive in order for the numbers to work out.

ke or k – The k value is a constant known as the Coulomb’s law Constant. This constant is based on the medium which separates the two charged objects. Each material (i.e. water, air, etc.) has its own specific Coulomb’s law constant. The units for this constant are N * m^2/C^2 where N is Newtons, m is meters, and C is Coulombs. This crazy unit is only chosen to cancel as the m^2 cancels out the squared distance on the bottom of the equation and the C^2 on the bottom cancels out the C^2 unit that comes from multiplying together the two q values. This leaves us with Newtons as our unit of force.

r – This r value is sometimes depicted with a “d” but it represents the distance between the two objects in meters.

Let's explore with an example:

From https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/estatics/Lesson-3/Coulomb-s-Law

“Suppose that two point charges, each with a charge of +1.00 Coulomb, are separated by 1 meter. Determine the magnitude of the repulsion force.”

We are assuming that the k value is that of the air which equals 9.0 * 10^9 N * m^2/C^2

What we know:

q1 = 1.00 C – this is described when the problem says assume there are “two point charges, each with a charge of +1.00 Coulombs”, meaning that the q1 charge is +1.00 Coulombs. In this problem instead of describing the charges as being applied to an object, we are imagining them coming from a center point of each so that we can calculate an exact distance. Almost every problem will use a point charge on an object as it allows for this exact distance to be found.

q2 = 1.00 C – same reasoning as q1

r = 1.00 m

k = 9.0 * 10^9 N * m^2/C^2

Find: F = ?

Plug in:

F = (9.0 * 10^9 N * m^2/C^2)*((1.00 C)(1.00 C)/(1.00 m)^2)

F = (9.0 * 10^9 N * m^2/C^2)*((1.00 C^2)/(1.00 m^2))

F = 9.0 * 10^9 N

By solving this equation we can now calculate that the force at which these two objects would repel each other is 9.0*10^9 N based on their charges.

A Real Example:

From https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/estatics/Lesson-3/Coulomb-s-Law

While in the last example our unit of charge was whole Coulombs, more often we see this charge in terms of either nanocoulombs or microcoulombs

1 Coulomb = 10^-6 microcoulombs (µC)

1 Coulomb = 10^-9 nanocoulombs (nC)

From https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/estatics/Lesson-3/Coulomb-s-Law:

“Two balloons are charged with an identical quantity and type of charge: -6.25 nC. They are held apart at a separation distance of 61.7 cm. Determine the magnitude of the electrical force of repulsion between them.”

assume k constant is that for air

What we know:

q1 = -6.25 nC convert to Coulombs – 6.25 * 10^-9 C

q2 = -6.25 nC convert to Coulombs – 6.25 * 10^-9 C

r = 61.7 cm convert to meters – 0.617 m

k = 9.0 * 10^9 N * m^2/C^2

Find: F = ?

Plug in:

F = (9.0 * 10^9 N * m^2/C^2)((6.25 * 10^-9 C)(6.25 * 10^-9 C)/(0.617 m)^2)

F = (9.0 * 10^9 N * m^2/C^2)((3.91 * 10^-8 C)/(0.381 m^2))

F = (9.0 * 10^9 N * m^2/C^2)( 1.03 * 10^-7 C^2/m^2)

The two balloons repel each other with a force of 9.23*10^-7 N. We just solved a real life example! Now you can go on to the next lesson to learn about the two types of electricity. Make sure to check out our sources for more information and examples

Sources used:

Blom, J. (2020). What is electricity?. What is Electricity? – SparkFun Learn. https://learn.sparkfun.com/tutorials/what-is-electricity/all

PHET team. (n.d.). Build an Atom. PhET. https://phet.colorado.edu/en/simulation/build-an-atom

PHET Team. (n.d.). Coulomb’s Law. PhET. https://phet.colorado.edu/en/simulations/coulombs-law

The Physics Classroom. (2018). Physics tutorial: Coulomb’s law. Coulomb’s law – The Physics Classroom. https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/estatics/Lesson-3/Coulomb-s-Law

Wang, J. (2023, January 30). Sub-atomic particles. Chemistry LibreTexts. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Supplemental_Modules_(Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry)/Atomic_Theory/The_Atom/Sub-Atomic_Particles